Simulators can not only help a driver learn an unfamiliar track, but can be a reasonable alternative to seat time as well.

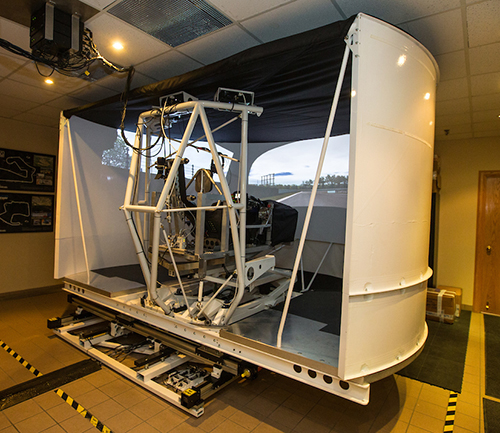

Mazda’s factory racers in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, the drivers of the Mazda RT24-P prototype, have access to one of the most advanced simulators in the world, the Driver-in-the-Loop (DIL) simulator at Muiltimatic’s Toronto, Canada, headquarters. That simulator cannot only simulate tracks with laser-scanned maps that reproduce every bump, but also accurately reflects the effects that setup changes have on the car so that the team knows what direction a particular adjustment will have in the real world. While the typical club racer doesn’t have access to such advanced equipment, the typical simulator setup can pay big dividends in a racing program.

Learning new tracks is part of it, but getting plain old, not-quite-old-fashioned seat time is a big thing as well. Simulator time is cheap compared to actual track testing, so if they can achieve similar results, that’s a bargain.

“Imagine for a test day, a big change could take an hour; a smaller change is 5, 10, 15 minutes,” says Oliver Jarvis, driver of the No. 70 Mazda RT24-P in IMSA. “The DIL simulator allows you to do a full spring sweep or roll bar changes in a matter of seconds. While the changes are realistic and they do give a feeling, what you have to be very careful of is that you really focus on what the change does and you don’t focus too much on car behavior. You don’t want to set the car up for the simulator; you need to understand what the changes do and then…apply them once you get to the racetrack. It’s more gathering that knowledge, so when you arrive you’ve got certain tools that you’ve already tested, you know exactly what they do, that you can plug straight into the car.”

The average home setup likely isn’t as sensitive as the Driver-in-the-Loop simulator. And while a setup change in iRacing or Asseto Corsa may reflect the general concept of what the change will do in the real world, those programs aren’t tuned to the level of the advanced simulators race teams use. But there is still plenty of benefit to a home simulator setup.

The average home setup likely isn’t as sensitive as the Driver-in-the-Loop simulator. And while a setup change in iRacing or Asseto Corsa may reflect the general concept of what the change will do in the real world, those programs aren’t tuned to the level of the advanced simulators race teams use. But there is still plenty of benefit to a home simulator setup.

“For myself, it’s only recently that I’ve started to use a simulator to its full potential,” says Jarvis, who uses a basic setup at home. “As a driver, you can learn so much before arriving at a racetrack – and this year, with the majority of tracks being new to me, going to the DIL beforehand means I’ve been able to learn the track and get up to speed extremely quickly. It helps you find the racing line, it helps you get into a rhythm.”

“For the average person, the [simulator] games are so good and so realistic that they’re doing the majority of what you can do on the DIL without the ability to really delve into them and find the details on the setups. It’s more useful for a driver to learn tracks and learn how to drive,” he adds.

Tristan Nunez, who has been with the Mazda program for several years and is familiar with the tracks at which IMSA races, has watched Jarvis and fellow newcomer Harry Tincknell use the DIL to learn new tracks and get up to speed quickly. But he and some other drivers use a simulator to model the stress they feel in a real race, or just get seat time they couldn’t otherwise manage due to time, money or logistics.

“I have a simulator rig in my house – a simple, wheel, pedal and seat with a three-screen monitor running iRacing,” Nunez says. “I try to be on it an hour a day just getting seat time. That’s what it comes down to at the end, seat time. That’s how you get better, that’s how you get more comfortable with the car.”

ACCESSIBILITY

ACCESSIBILITY